Holistic Management Fundamentals - Community Dynamics

Complexity creates stability in community dynamics

In the study of Holistic Management on our Fundamentals Course we introduce the 4 ecosystem processes, the water cycle, the mineral cycle, energy flow and community dynamics. In this final in the series article we look into the 4th process of community dynamics in more detail.

What Are Community Dynamics?

Community dynamics refer to the interactions between species and the changes in biological communities over time, in other words, how the various life forms interact within a system. These relationships shape the structure and function of ecosystems, influencing biodiversity, resilience, and productivity.

A landscape is shaped by organisms—plants, animals, microbes, fungi—all playing their role in an ever-changing ecological dance. Their relationships shift in response to environmental conditions, competition, cooperation, and natural disturbances.

Three key forces drive community dynamics.

Succession is the natural progression of plant and animal communities over time, moving from bare soil to a complex ecosystem.

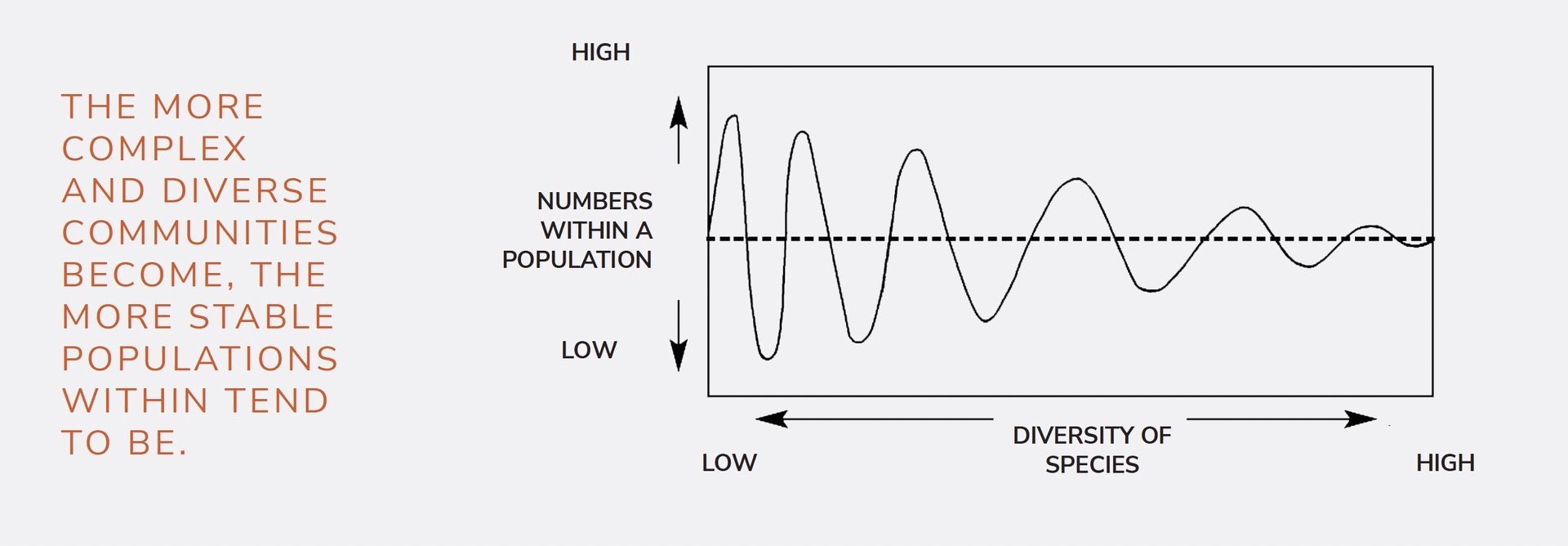

Biodiversity determines an ecosystem’s stability—greater diversity fosters resilience, while low diversity makes systems vulnerable to shocks.

Trophic interactions refer to the flow of energy and nutrients between producers, consumers, and decomposers, influencing how productive and self-sustaining a system can be.

If we step back and observe nature with a wide lens, we don’t see a collection of isolated species. Instead, we see an intricate web of life, constantly shifting and evolving. Every organism is part of a dynamic system, shaped by interactions and relationships that determine the stability and productivity of an ecosystem. This ever-changing balance is what we call community dynamics, the fourth pillar of Holistic Management.

Understanding community dynamics is essential if we are to restore degraded landscapes, regenerate soils, and create abundance in the ecosystems that support us. Without it, we risk disrupting the delicate yet resilient balance that has sustained life on Earth for billions of years.

The Role of Disturbance: Necessary Change

Change is not just inevitable—it is essential. Disturbance plays a key role in shaping ecosystems. Fire, floods, grazing, and even storms create opportunities for renewal. Without periodic disruption, ecosystems can stagnate or degrade.

One of the most powerful natural disturbances is herbivory. Historically, large herds of herbivores moved dynamically across landscapes, grazing intensively before moving on, allowing plants to recover and soil life to flourish. In their absence, ecosystems often shift in unintended ways, leading to desertification or biodiversity loss.

Holistic Management uses planned grazing to mimic these natural cycles, restoring the function of herbivory as a regenerative force rather than a destructive one.

Brittle and Non-Brittle Environments: A Key Distinction

Community dynamics differ greatly between brittle and non-brittle environments. These terms describe how moisture is distributed and how organic matter decomposes.

In non-brittle environments, typically humid regions with regular rainfall, plant material decomposes rapidly, and ecosystems recover more easily from disturbance. Here, biological communities are often more stable, and natural succession happens at a faster rate.

Brittle environments, such as grasslands and semi-arid regions, receive erratic rainfall with long dry periods. In these landscapes, decay occurs through oxidation rather than microbial breakdown, making it harder for nutrients to return to the soil. Community dynamics function differently here, as natural systems rely heavily on grazing animals to stimulate plant growth, cycle nutrients, and maintain biodiversity.

Holistic Management recognises that the same approach will not work everywhere. In non-brittle environments, overgrazing can be a significant issue, whereas in brittle environments, undergrazing or the absence of disturbance can lead to ecosystem collapse. By aligning land management with each environment’s natural patterns, we can restore healthy community dynamics and create more resilient landscapes.

The Loss of Community Dynamics and Ecosystem Collapse

When we fail to understand or manage community dynamics effectively, we create fragile, degraded ecosystems. Many agricultural landscapes today suffer from a loss of biodiversity, disrupted grazing patterns, and broken predator-prey relationships.

Overgrazing and undergrazing both degrade land, not because of grazing itself, but due to mismanagement of timing and intensity. Removing key species, such as wolves or beavers, can unravel entire food webs. The widespread adoption of monocultures, replacing diverse plant communities with a single crop, leads to soil depletion, increased vulnerability to pests, and reliance on artificial inputs.

When these imbalances persist, they result in desertification, where once-fertile land turns to dust, unable to support life.

Restoring Community Dynamics with Holistic Management

Holistic Management provides a way to work with nature, rather than against it. By making decisions through a Holistic Context, we can design resilient, diverse, and productive landscapes that regenerate rather than degrade over time.

Restoring community dynamics requires reintroducing diversity at every level—both in plant and animal communities. Increasing biodiversity, above and below ground, enhances ecosystem stability and resilience. Thoughtfully managed livestock can mimic natural grazing patterns, restoring grasslands and improving soil health. Reintroducing key species, such as predators, pollinators, and decomposers, helps maintain ecological balance and promotes regeneration. Allowing ecosystems to recover through properly managed disturbance—rather than suppressing natural processes—ensures long-term stability and productivity.

Learning to steward

Life is not static; it is constantly moving, adapting, and renewing itself. Community dynamics shape our world, influencing whether an ecosystem thrives or collapses. When we understand this process, we see that no landscape is truly fixed—only managed well or poorly.

Holistic Management provides the tools to regenerate land, restore biodiversity, and create abundance. By making decisions within a Holistic Context, we align human activities with the natural systems of life, ensuring that our landscapes remain productive, resilient, and self-sustaining for future generations.