Got Woodland? Maybe you need pigs?

Agroforestry with Pigs:

A Woodland Enterprise Model

We explore the role of pigs in regenerating and maintaining woodland whilst generating income -- please find the recording & transcript below

As more UK farmers explore regenerative principles and look to stack enterprises that align with their land’s natural potential, woodland pig farming is emerging as an option with surprising depth. Blending ecology, animal husbandry, and premium food production, this model offers both environmental and economic rewards—particularly when grounded in agroforestry.

At Beal’s Farm in East Sussex, Melissa Masters and Phil Beal have taken a bold approach: rearing rare-breed Mangalitsa pigs beneath mature oak canopies, using the trees not just for shelter but as part of a living, working ecosystem.

Their work is now the focus of an Innovate UK-funded research project—designed to study how pigs can be integrated into agroforestry systems in ways that regenerate soil, enhance biodiversity, and produce exceptional food.

The Mangalitsa pig, with its distinctive woolly coat and richly marbled meat, is already well known among charcuterie producers. But this isn’t just about niche produce. The team at Beal’s Farm are proving that when managed with care, woodland pigs can serve a wider purpose: maintaining tree cover through natural rooting and coppicing behaviours, fertilising soils in situ, and activating underused woodland into a productive, balanced system.

The project, in collaboration with Cranfield University and AgriSound, is taking a scientific lens to this traditional-meets-modern approach. Key areas of study include:

Soil Health – Through 80 samples analysed for microbial life, carbon content, and nutrient balance

Pollinator Biodiversity – Using bioacoustic detection to monitor insect activity

Tree & Habitat Monitoring – Assessing the effects of pig activity on woodland structure and regeneration

Animal Welfare – Behavioural tracking and welfare protocols, comparing traditional vs. woodland-based systems

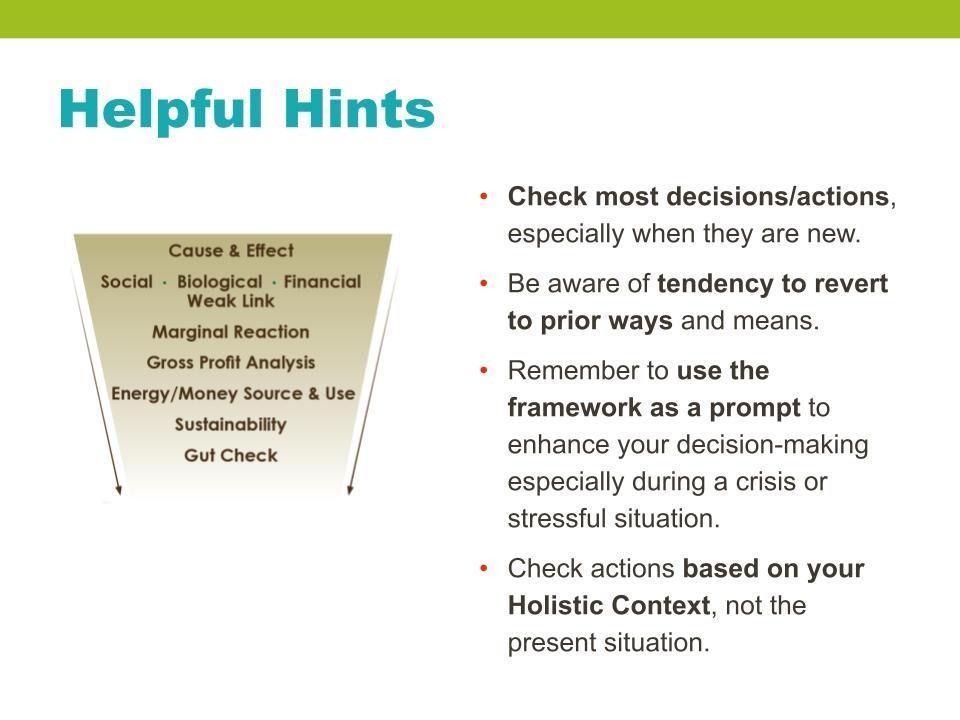

For those practising or considering Holistic Planned Grazing, this work adds valuable insight into how multi-species and integrated systems can be extended beyond open pasture. It also opens the door to stacked enterprises—using underutilised woodlands not only for pigs, but potentially for fruit, nut, or timber production alongside.

What’s compelling is that this isn’t theory. Beal’s Farm runs a profitable charcuterie business that supplies everyone from local cafes to Michelin-starred chefs, all grounded in the narrative of field-to-fork provenance and agroecological integrity.

This project isn’t just producing premium food—it’s generating data, validating ecological assumptions, and building a replicable model that other farmers can adapt. As part of 3LM’s mission to support land managers in designing holistic, regenerative systems, we believe this is one to watch closely.

Woodlands aren’t just for walking or are to be thought of as a non productive part of the farm, with a reframe, they can be the future of resilient, profitable, nature-aligned food production and conservation all in one.

Video of the webinar from our YouTube channel below

Full Transcript

Welcome, everyone. Thank you for joining us for tonight's webinar. This is the 1st of April, 2025. My name is Sheila Cooke and I'm the hub leader for 3LM, which stands for Land and Livestock Management for life. We are a hub in the Global Savory Network. And we're the hub in the UK and Ireland.

So nice to have you here. We've got a really wonderful webinar with Melissa Masters and Phil Beal From Beal’s Farm. On the topic of woodland pigs and charcuterie. And with that, I am going to turn it right over to Melissa and Phil.

Hi, everybody. Glad that you were able to make it and to, have a listen to what we have to say. So as Sheila said, I'm Melissa, and this is Phil and I, we, we own, a business called Beal’s Farm Charcuterie. And, we rear pigs as well, Mangalitsa pigs. So I'll just click through. The slides as we go through.

Sheila has said that perhaps there might be some relevant questions that we have a pause for, but otherwise, I think questions generally are being held to the end for the Q&A. Okay, so mainly what we're here to talk to you about, as well as our pigs and our business is, the idea of agro forestry.

Some most of you probably, I would imagine, if you're a farmer based, are used to that term. But for those of you that aren't, it's a sustainable land management system that is used to create environmental, economic and social benefits, basically. So the picture, above obviously shows the variety of ways that agroforestry can be implemented. and for the benefit of all around not just in terms of livestock and animal feeding, but obviously trees just generally, are used also for all sorts of other environmental, elements of building things and food and medicines and providing shade and other plants to be able to grow around.

From, from obviously the soil that trees have in woodlands. Basically, the specific agroforestry element that, we want to talk to you about is, is to do with the diversification of the land use. And actually incorporating trees alongside livestock is what we're involved with. But obviously crops is another area that, that, agroforestry is useful. It's also to do for us with enhancing sustainability, improving soil fertility, reducing erosion and increasing resilience to climate change obviously a very big topic at the moment.

The economic benefits, well, basically, for us, for anybody else who, is thinking about perhaps using woodland area for rearing livestock, it, it comes about by being able to give potentially additional income. Because woodland reared livestock really does. The meat from it does appeal to a very high value niche type market place out there, because it's a premium product basically that comes from woodland rather than intensive pig farming. You've got something that really is quite, considered to be quite a special product.

Also, obviously there's the environmental impact that agro forest can agroforestry can benefit the environment with and that's to do with, the carbon emissions, obviously, preserving the wide variety of biodiversity that, that goes on in woodlands and forestry areas and reducing the need also for chemical inputs. Okay. So basically Beals’s Farm is Phil and I we run a family business. We specialize in artisan British charcuterie making, and we have our own herd of 100 plus woodland reared Mangalitsa pigs.

We've been going about 12 years. Yeah. So. So we are here in 2024, with really sales doing quite well in Britain, I understand a few of you are perhaps viewing not from the UK. But yeah, charcuterie is definitely, on the up and up as far as, the UK market goes. So what we do is we specialize particularly in Mangalitsa pork. I'll get on to that particular breed of pig in a little while. But it's a rare breed, and it's a rare breed pig that's very much renowned for its, the marbling through its fat, through its lean.

It has fat marbling all the way through, making it very, flavorsome. And it's used for artisan products we use traditional craftsmanship, basically artisan techniques. This is something that we learned in Spain, about 12 years ago. We lived in Spain for the ten years previous to that. So what we produce is very authentic salamis and chorizos a wide variety of different, air dried meats. And we hand produce these we cure and we air dry using artisan techniques. Obviously, our sustainable farming practices we're very, very proud of because our pigs are raised in a completely natural habitat.

That's in near Tunbridge Wells, which is south of England, on an estate called the Eridge Park Estate. And the pigs get to forage completely freely in the woodland area. And through that, we believe that we are enhancing. And hopefully we'll be able to prove this through a study that we're involved with, that it does enhance biodiversity. And we see with our own eyes that it definitely promotes animal welfare and improves the meat quality as well.

So we've got a retail customer base with an online shop, and we also sell to trade customers across the UK and the channel to various restaurants and hotels. In fact, probably 90% of all trade is to the trade, 90% of all sales, with about 10% from we made a decision, a number of years ago to predominantly sell to restaurants, really to, to kind of, yeah. Just because that seemed to be where the market was the best place to sell for us.

But retail is picking up definitely. We also do a lot of collaborations, with top chefs. We've had, a couple of, celebrity chefs who've actually asked us to bespoke make products for them and Phil will talk a little bit about that later. But yeah. Mangalitsa pigs are definitely regarded to be, to be a prime product as far as kind of, hospitality goes. So using pigs in woodlands, we've got some key benefits and considerations to have, to go through with, with you, as far as benefits goes for the land, it definitely encourages a more open woodland structure. That's what we've found. We've had our pigs in woodland here for about three years now.

So this is observational that we've, we've seen going on as the livestock, have been living in that area, it improves light penetration and promotes a healthier forest floor. It supports natural regeneration of the native tree species that we have. And we've got mainly oak, beech. We've also got silver birch, and a few others as well. Because what the pigs do is they naturally (inaudible) the land area and they disturb all of the compacted soil, which in turn creates bare soil patches that then encourage more tree regeneration.

The pigs also help to control invasive species. So we've got a lot of rhododendron, in the woodland where our pigs are, a lot of bramble. And their rooting behavior really does keep all of that back. And also having the pigs there also enhance the wildlife habitat loads of, different types of ground conditions is what, what they produce through their foraging in certain areas and obviously the ground level plant diversity and the wildlife germination is encouraged because of that. When they root with the snoot snouts, they're obviously aerating as well, the soil. And that actually helps to, make those compacted layers break up and obviously improves the ecological health system that's actually going on in the soil. Yeah.

So basically it adds an overall ecological value to any woodland. I'm really aware that for a lot of people (inaudible) seeing pigs in woodland is just going to ruin things. And, and, you know, just munch on all the tree bark and just destroy all the areas. But this is this is absolutely not the case. I really want to reassure you that. And I'll show you visually, what we have experienced, taking some photographs so that you can perhaps be a little bit more confident if you've got woodland area yourselves.

So here's an aerial shot of, one of the areas that our pigs live in. It was taken probably only a couple of months ago. So here in the UK, it's, it was just end of winter, basically. So obviously a lot of the ground hasn't got, new growth on it. But you can see that there's lots of, bushes, lots of trees. There's our topic. There's it's got to be able to show you that if pigs were not occupying ...occupying a particular area, the woodland, the one on the left is what it would look like. So that is just simply, woodland area.

No pigs have grazed on, on the picture on the left at all. You've got quite coarse grass coming through. You've got some quite boggy areas where obviously water collects. The picture on the right is where some pigs have, obviously been in for a few months. And again, you'll see throughout these pictures that I'll show you that we've got a little bit of tree, a few trees that they've rooted and come and, coming down. But I'll show you a little bit later that that's really young saplings and, on the whole that they, they pull up, which is actually beneficial to the woodland. Pictures here that show an area after six month usage of having pigs in the paddock.

So obviously they've gone right the way through the paddocks turned all of the earth over munching in the meantime on an awful lot of beneficial things for themselves. So, apart from fruits and berries and grubs and all sorts of stuff like that. And what we have is a rotation system. So basically four months after resting a paddock, what you then get is the picture on the right showing you very much new fresh grasses coming through, little bit more meadow like I would suggest if you actually look at it. And the recovery is particularly good.

The photo on the right is probably after a spring summer duration. So perhaps you wouldn't quite get so much regrowth after a winter period, but certainly a spring and summer period of resting. That would be the case. And there's quite a big difference between those two pictures and quite a speedy recovery. Okay, so the benefits are so the livestock is really what I want to talk about next. So obviously the pigs are thriving in terms of living in a very natural habitat for them. So what this means is they’re going to have very natural behavior patterns as well, rooting for them and wallowing, making their own wallows, in areas that they want to be in areas that water would naturally gather, they're promoting, it promotes for them an environmental enrichment, which absolutely helps with their welfare. There's no need to put nut balls in or anything for them to be able to have things to do to keep their mind occupied, occupied, because it's all there naturally for them.

They also get the benefit, obviously, of certain foods. They've got acorns and roots and vegetation that are going to improve. Not only the pigs health, but actually improves the... the meat flavoring as well. We estimate that roughly, particularly in, in, in summer, autumn time coming through as well, is that you're going to get, a lot more, acorns that are going to drop from, from the trees. So for us, roughly, we've got a reduction of about 20% in terms of feed costs. So, you know, for that, that's that's quite a lot for, for farmers, generally speaking, I think and certainly we found that it benefits us, them having that, that additional supplementary food that they can gain naturally. Um, acorns are obviously quite poisonous.

We don't happen to have cattle where we are, but obviously there's quite a few, public ground grazing areas that perhaps might have ponies or farmers might have cattle as well. So the acorns, the pigs are obviously eating, whereas they might be left down for other stock. That may well, find that they got belly problems because of it. The outdoor woodland systems as well can reduce stress. We find obviously they. Absolute (inaudible) makes 100% difference to the flavor of the meat. And in addition to reducing stress, it's also going to increase all of that natural goodness by getting dietary wise is increasing the immune system as well of the pigs.

So we find that really antibiotics is not something that comes into play as far as as far as pig health goes, we did use to raise our pigs on, in a field, a big field. And definitely there's, there's, there's really no necessity because they just seem to be, have much stronger immune systems. So the natural livestock coppicing that I was talking about a little bit earlier, you can see on the bottom we've got a, drone shot of a group of pigs in a paddock it was just feeding time. So actually, that's why they're pretty much hovering quite close to the fence. But let's have a look. This again, is after about a six month period of being in this paddock, you've got, the most of the trees are still standing. You've got a few on the picture on the right, the upper right picture that have been knocked over.

Generally speaking, feeding happens. We put feed down quite close to the roots. So it's almost an intentional thing that we actually want to happen because these are thin, small silver birch saplings that we actually want them to be coppicing. So you can see on the pic from the right the roots showing on on a couple of the ones at the bottom on the far right. So they will slowly themselves obviously loosen each time the pigs are feeding and rooting and and doing all of their, their, stuff with their snouts picking up all of those young saplings that we actually don't want to be there because what we want is more light penetration coming through from the canopy, to be able to then create that kind of meadow grass to recover and come back. Excuse me.

So these are just a few a few pictures for you to get a visual of the kind of welfare for them and how naturally they are living. They're moving through the woodland as they wish, going where they want. Even in winter. The one on the far left is obviously when it was snowing here. During winter, our pigs are very hardy. You know, there are other breeds equally that could could sustain themselves quite well in the woodland. We do give them an arc in each of the paddocks (inaudible) quite often they decide not to actually sleep in them more often than not. Excuse me. Okay, so as far as benefits for farmers go, I would suggest that certainly in terms of income, there is potential that if you use woodland area for livestock with the agroforestry methodology, then you have got, basically public demand being favored in your favor.

There's obviously a focus at the moment on enhanced environmental sustainability to improve, pig raising welfare, to produce food that's much more field to fork. its all desired both by retail, customers and by trade customers as well, as an increased market opportunity. And not only that, obviously, it's also reflective that you can achieve a slightly higher premium price because of that, because of the the ethical nature that you're actually raising your livestock by. We've obviously got the increased feed efficiency that I mentioned before, that 20% in terms of, feed going into the animals. There's also been a couple of studies done that actually show that, pigs will emit less greenhouse gases because it actually results in a lower nitrogen in their diet and phosphorus excretion that's created by them. And in addition to that, obviously, for an awful lot of people, I'm not sure, again, what it's like in Europe and worldwide, but certainly in the UK there are definitely integration with potential.

There's integration potential for funding opportunities. There's a lot of woodland pigs systems that, well, a woodland pig system, does align with an awful lot of agro forestry and conservation or stewardship type schemes where perhaps funding is available as well. In addition to that, there's lessened veterinary costs because they're healthy and as I said, of antibiotic use, because of increased immunity. So some considerations for anybody out there that's thinking about potentially using a small strip of woodland and to be able to keep livestock in, obviously, seasonality is perhaps a consideration that you might not think about.

But as far as the grazing goes, obviously autumns are really good time of year depending on where you live. I don't know, how many of you, like I said, watching from outside of the UK. But grazing does occur all year round with our pigs, so there's no doubt about that. In terms of breed choice, obviously, traditional and hardy breeds are going to be much better for woodland living. We've got, Mangalitsas But equally, pigs like Tamworth and Gloucester old spots are very well suited to woodland life. The management obviously of the agroforestry system that you use is very important. You do need to rotate it, rotate your paddock systems just in the way that you would if you were raising pigs in a field, because overgrazing and excessive root rooting certainly would be a problem.

So we tend to keep to a certain period of time that pigs are allowed in a particular area of the woodland, and that's really a maximum of about six months. I'll talk to you later about a little bit about a study that we're looking at in terms of density and how many pigs you would put in X amount of square meters to try and find that optimum level where it's, where it's helpful not, destructive to any woodland area. If you were to get in for a year in one spot, then obviously they are going to do some damage. So so the management of the areas that you're using and keeping them rotated is still really important. In woodland, as much as it is with a field or grassland.

As far as the infrastructure of actually building an area, that's going to be quite important and does put in it does need a little bit of effort to be put in. Because obviously you need some strong fencing. You need water access and obviously shade. Well, shade you're likely to get if you're in woodland, but you've got to make sure that, well, the pig section or isn't, isn't completely open. So the type of things that we do to be able to create or put our paddocks in the woodland, that, the picture on the top right is where, there's quite a lot of rhododendron there, and that would have been cleared with a bit of chain sawing, just to bring back some of that foliage and be able to clear a straight line, to be able to put fencing up. And then the picture on the top left is obviously posts that we’ve had delivered So we use chestnut posts they’re normally five foot 6 or 6ft tall.

We tend to try to get, quarter chest chestnut posts rather than full round ones or half split ones. And then they will get, they will get put into the ground, bumped into the ground. sorry.... my wording normally probably about a foot down. Yeah. A foot down into into the, the woodland floor obviously is quite a lot easier if you are to do that when the ground is slightly, slightly damper. So I probably wouldn't recommend that anybody tries to actually build paddock areas in woodlands in the middle of the summer because the, the ground is obviously going to get very hard. Most of you probably already know how to do fencing anyway for farmers. So this is kind of I don't want to teach you to suck eggs or anything, but we use electric fencing and just shows our insulators that we put into the into the posts, and then we run batteries... from batteries, electric fencing all the way round. Sometimes we use green posts depending. Now pigs will still potentially move any, dead bits of wood.

And so sometimes your electric fencing obviously can be affected by that. So obviously maintenance is quite important. You check all of that. Equally they can route, the earth up against the wire as well, so a couple times a week or so, really walking the fence lines and checking that they're clear. We have had escapees before now, but generally speaking, if you maintain and you keep an eye on it, they don’t overall, it's... it's a system that works. Definitely. We find here. Okay. So why the Mangalitsa pig? For us, in particular, the Mangalitsa is it's part of who we are. It's part of completely why we fell in love with what we do.

Therefore, their breeding guardianship is really important for us. They are a rare breed pig here in the UK. Introduced into the UK in 2006. So I'm just going to do a couple of slides that hopefully you'll find interesting. As far as the history of the Mangalitsa pig guys because it's not, some of you may well, none of it, but I do come across people who who don't know what a Mangalitsa pig is at all. And I think it's very strange when they look at them because they're so curly coated. So a little bit of history about the Mangalitsa... It's basically a partnership that the Mangalitsa pig goes back, you know, eight, 8000 years to Asia, even before coming to Europe. There's three varieties of the the Mangalitsa pig... There's a blond, there's a red, and there's a swallow belly. It's black on top with a kind of cream underbelly, but it's a very unique pig.

This is genetically, it's quite a unique pig as well. It has marbling, as I said, that goes through the lean of the meat and, used to be known as a hog with a lot of lard, because that's exactly what it produces for us and lard for us is is very important. The fat content for us as charcuterie producers is absolutely vital. So, it's kind of, obviously as a piglets looks quite unusual. Born with stripes. Loses the stripe obviously as it gets older so very originally, obviously between the first and 13th century, roughly, roughly AD the pig came from China and and the Tang dynasty. And for those of you perhaps, maybe will know of the Silk Road. But it was a very, very important trading route. And so the pigs used to come across from China into Europe. ...all the way, basically.

So this is a photo of some very, you know, boar, like, looking, Mangalitsa pigs. If you look at the piglets, they really don't look that different to ours When I show you a photo a bit later of our piglets, the adult there probably looks a little bit more wild boar than ours do But this is obviously a much... from from a long time ago. These types of photos of more wild boar looking. But these. This is how they were. They were herded down the silk Road. The links with the UK kind of came obviously once they were in Europe, mainly in Hungary and Austria. So basically, although they thrived for a long, long time, by the time the 1970s came along, they actually the Mangalitsa pigs got down to as little as 200 pigs. And that's in part because obviously by the time it was 1970s, the whole the whole idea of humans eating things that were really fatty was something that was changing.

Everybody was turning into into wanting lean meat. And Britain, when they did get down to those kind of numbers, in the 70s, Britain did help out by sending a pig that is extinct currently in the UK called the Lank Lincolnshire Curly Coated Pigs. So we did have one that was a curly coated pig, but it's extinct now, so, UK actually helped Britain actually helped by sending some of those over to boost the Hungarian numbers. And then in 2006, we, we had Mangalitsas imported back into the UK. So, a Mangalitsa It's a pig. It's a little bit different in terms of its kind of production. They have smaller litter sizes than perhaps your average commercial pig and many other breeds. Actually, 7 to 9 piglets per litter is all that they produce.

Gestation period is pretty much the same. We wean all pigs, from, at about 12 to 14 weeks. Obviously commercial pigs are a lot earlier than that, but that's kind of a preference. We probably could wean earlier, but we prefer not to. And their age, when they go to slaughter averages sort of nine months to a year old. We we do keep some of our pigs up to 2 or 3 years for special reserve charcuterie products. What happens is the whole quality of the meat increases yet again. If you have an older pig, not on any of the cuts cuts larger, but they also have a change in the kind of, texture of the marbling in the fat that goes through So they are slow growing.

And one might think, therefore, that, you know, well, that's not very good for production if you're a farmer, but as, we'll go on to show you the, the premium price actually is, that much higher that it kind of really is worth it, even though they are slightly slower growing. Pig. They're obviously, the yield is a high fat content and they're very, very calm pigs and well suited to outdoor, woodland systems. Obviously no video is complete or no presentation is complete without just at least 10s of me showing you, what they like at a one day old. So you can see there the real wild boar kind of stripe that goes through them. Very, very hardy pigs, you know, ready to go, deal with the outside world. Really within about 4 or 5 days normally they're out of their arcs. Okay.

I'm just going to, hand you over to Phil to let you know, a little bit about the charcuterie that we produce. Hi, everybody. Thank you. Melissa well done, so a little bit about what we do. The end product. This is after we take the pigs to slaughter. So there's a few pictures in front of you of our hams, various sliced meats, spicy choritzo etc.. So this is a kind of a brief look. Well, that looks quite complex. The breakdown of the pig itself compared to your regular, commercial breed. So on the left hand side, we've got the traits or features. So monounsaturated fats. Very important. Very good for your cholesterol Mangalitsa pigs are much higher in this. This is not only good for your cholesterol, but it makes the fat much creamier and a much more meltier texture.

We get a lot more fat layers on top, which, you know, in the past and even still today, people are quite wary of a lot of fat. But ultimately the fat is where the flavor is. And for charcuterie, when you air curing and air drying products for up to 18 months, when you get to the end sliced product, it really leaves a creamy texture in your mouth and cleanses your palate straight away. You get a lot more fat on on the abdomen, which is great for your bacon's and your pancettas The intramuscular fat just just like a good piece of beef has good marbling in your roast dinner. That's what we're looking for in the lean muscles of our pork, so that equally, when you come to air dry, it acts a bit like a spring and a sponge to slow down the drying process.

So you get a really even texture at the end. the fat in the... the fat everywhere. I mean, I could read them fat all day long. The fat is everywhere in Mangalitsa for and it's running on the outside. And that really helps, not only just for the charcuterie but for raw Mangalitsa pork as well. When you're roasting it or pan frying it, it just crisps up perfectly. So juicy and tender. Amazing. (inaudible) All right, so it's the past ten years for us after coming back to the UK. This was just a step by step process. Back in 2012, we purchased our first six Mangalitsa pigs, which we had to breed and then wait for them to get pregnant and then wait for them to deliver their first litters. So during this period in 2013, we were practicing many of the skills of making charcuterie, which we learned in Spain using local wellfare, local pork from farmers markets and local farm shops.

At the same time, you starting to put the feelers out as to where you're going to sell this product when you finally nail it down, making it in this country, obviously back in 2014, it wasn't very well. When we started doing farmer's markets, I would explain to people that we produced our own charcuterie, and the tasters that they were eating were from our own pigs. But occasionally at the end, the customers still say, has this come from Spain or France? So it's taken many years to get it into the culture of this country, which is building much quicker now. We're always expanding the product range, always adding new product lines.

Culinary tastes change, things come in favor. They drop out of favor. When we came back cooking choritzo was a hot topic. Now, cooking choritzo so isn't so much the hot topic. So you can't sit on your laurels when you're producing products to always keep looking, to find something new and interesting to put in front of the customer. The main thing, obviously, is the nose to tail, which basically means we try and use every part of the pig. So that product range is going to be mainly depicted by what we can use for that pig, and what product you can go into. In 2016, we started entering our products in awards.

This is something to give you some self-confidence and just to gauge where you are with your peers within the sector. We happen to do very well at this, and this came to a pinnacle in 2018 when out of 450 products, our air dried ham won the best overall product. That was great. Fantastic. That does a lot for consumer confidence. If they can see that you're backed up by some certification. But ultimately the real challenge up the line. If your customer likes what they taste, that's what they're going to buy.

Back in 2019, things started to change a little bit when we came back from Spain. Local produce was very important to people, but local didn't necessarily mean it was very good. So this kind of changed in 2019 to 20 to more about provenance, meaning where does the pig come from? How is it reared? What does it eat? How do you treat it? And this for chefs in restaurants and hotels, it's all about the backstory to this, the meal that they're cooking you. This now got a backstory to it. And this will be shown in a bit later.

That helps add a premium price to the product you're selling. We moved to Eridge Park back in 2022, so now we've been in a position to expand the herd, and we're doing that as quickly as possible. We're up over 100 pigs and over the next three years we hope to get that up to 250, 300. Obviously, Covid 19 ground hospitality to a standstill. It made everything difficult for everybody. I can, I'm sure can relate to that. And it's only really been in the past year. The hospitality, hospitality start to feel a bit more confident, even though it's not quite predictable for restaurants and hotels. What's going to happen three six months down the line.

Back to right up to last year... Like I say, we moved to Eridge Park Estate and that's where we managed to win the innovate and DEFRA research project to carry out on our woodland. So, so some of the people that we've, been noticed by whom we've worked with is we supplied quality Michelin star restaurants. Now, we made several TV appearances. We worked with quite a few celebrity chefs, but fortunately we worked with a lot of great chefs with celebrity chefs or just a local restaurant just down the road. We try and focus as local as possible, but obviously we're starting to attract further afield customers, so you never turn down a sale.

So the production, basically we do everything from rearing the pigs. The pigs come in, we butcher them. This is seam butchery which is different to standard butchery. So for charcuterie we're not preparing pork chops and steaks and roasting joints. We're taking out all the individual muscles, keeping them in their entirety then we’re going to be curing them. So we're going to be rubbing them salt and in their own bespoke, spice and herb mix, then they're going to be kept in that cure mix for one, two, three, four weeks, depending on the size. They're going to be kept in the fridge. They're going to come out of the fridge, they're going to be cleaned off, they're going to be rubbed in olive oil, wrapped in a collagen casing, put in a net strung up and hung away in the drying room.

Our drawing rooms are basically a little bit of the Mediterranean, so we're creating conditions that are slightly humid and a little bit drier. Obviously in the UK it's a typically wet and cold climate. We're looking for having and in drying room temperature of around 75 to 80%, humidity and a temperature of around 14 to 15 degrees, and we keep this stable throughout the duration. Smaller products like a small salami, will be in for 6 to 8 weeks, and then hams will come right out about a year or so later. So here's a quick breakdown of how long everything takes a day. The bigger hams we take up to a year and a half, a coppa, which is a whole neck muscle, can be anything from 5 to 7, eight, nine months. The lomo which is the whole loin, basically the eye of the bacon or pork chop 4-6 months, and so on and so forth, all the way down to something like a choritzo 3-4 weeks Now, what does making charcuterie do for your profit potential? A basic charcuterie products like salami and pancetta is that they're going to reap 100 to 150% added value. So basically whatever the raw meat value was, you're now increasing that by this percentage. The air dried products. So your hams, your coppas your lomos, now you're pushing up to a minimum of 300%.

And with some of our very big hams, which are aged for 2 to 3 years, this can even put up to a thousand 1,500%. And it's a long term investment, but it's a big percentage return. Hopefully this illustrates a case for converting the pork into something that little bit more special. In our case, charcuterie. So quick price comparison down on the left hand side. We've got the whole carcass and a few basic cuts like the chops, the belly, the shoulder, the roasting joint and the fillets. So for your standard commercial pig, something that's reared for about five and a half months, which will pick up in a supermarket, these are the kilo prices they’ve probably gone up a little bit now, because all meat prices are going up quite rapidly at the moment. When you come to fresh Mangalitsa pork.

These are the prices you can achieve per kilo. There's a caveat to this. You need to find your clients. So the research work that you need to put in here is to find the restaurants, find a high end butchers, find the online customers that understand what Mangalitsa pork is, what to do with it, and where the value is within it. We supply quite a lot of half carcass and carcasses to restaurants and, hotels, and they'll break it down themselves and then turn it into many dishes. Pork is known as the Kobe King of pork. A bit like it.

You've got Kobe beef. This is the best pork you can get in my mind, it's the most ethically sourced. As you've seen It's environmentally regenerative, healthy and delicious. It's rich in omega oils and high in monosaturated fats and that gives it that real creamy, smooth texture. And as I've been explaining, the restaurants love it and know exactly what to do with it. Back to you Melissa I'm just going to speed through this quite quickly because I realize some people might have questions and answers. So this is just very briefly about a recent, funding opportunity that we managed to get, which was about 40 K that came through from DEFRA and Innovate UK. So the idea is it's a project, 18 month project where we are actually going to test all of the soil pollinators and activity as well, pig welfare and the kind of impact that it has on the livestock as well. And (inaudible) our partners that are involved in this, they are Cranfield, Center for Soil Agri Food and Biosciences will be testing the soil throughout this 18 month project and actually looking at the analysis of the chemical composition and the changes that do happen because of livestock being in our woodland. And the same with the pollinator biodiversity.

That's also going to be, is tested through the picture on the bottom left, on the bottom right, which is basically going to, monitor all kind of, activity of any pollinators that come anywhere near where the pigs are. This is what obviously, we've we've been working in partnership with we had to design the project and a new area in our woodland area, and we're working together basically to hopefully give, some real scientific data at the end of the project, just in case anybody's thinking. I don't really like the idea of Mangalitsa pigs, even though we are very passionate about them. There are many hardy breed options for woodland grazing Tamworth, Gloucester Old Spots, Berkshires, large blacks, middle whites and there's probably others as well that you could include. So all I ask really for you is to perhaps consider. Have you got some agroforestry activity in your woodland that's going on?

Results in the left hand picture that I showed you earlier, and the right hand picture of potentially what it could become if you go ahead and raise some livestock in whatever small strip or large strip of woodland that you have, and that's it. Thank you very much for taking the time to listen to what, I've shared with you and Phil has shared with you. Thank you guys. Thank you so much, both of you. That was really, really interesting. Really well done. We've got a number of questions. I'm going to start right at the top. How do you deal with the impact of deer on woodland regeneration after the pigs have been through an area? Is is that an issue that you need to handle? There are a lot of deer on the estate. It also holds one of the. It's about the second oldest deer park, in the UK, so that it's not a day that doesn't go by where we walk past the deer. They tend to on enclosures that are regenerating.

I do see them in there, but it's very low impact. I don't think they tend to get on with pigs, and I don't think foxes get on with pigs too much, so they tend to pass through the woodland, but they don't really hang around a lot. I maybe see a couple that will be grazing, but no great herds. Obviously we've got the fence and it's not deer fencing But that boundary. maybe it's the smell? the smell of pigs. Not that it's really smelly there, they tend to be outside of that piece of woodland. For the most part. I've never noticed it incorporate any damage on any of the wildlife. So great part of our project. We have four full paddocks that are part of the project, and one of them is a control paddock that has no pigs in it at all. So again, there'll be an element of monitoring going on for, you know, what goes on with the deer grazing compared to an area that isn't grazed by them Great. Thank you.

The next question I know you addressed already, but, are the restaurants really willing to pay the value for what you're producing? Do you ever have any issues with them, barking at the price that you're wanting to charge? Or what? I don't mind. No, I would say generally I do kind of all the invoicing and, deal with kind of any administration and payments and stuff like that. I would definitely say that there, when I'm marketing, there are a small handful of people that will say, I don't think I can afford it, but they are generally, you know, it's it's generally because they have a fairly low budget for their menus anyway, across the board. It's not just our product, it's just generally they perhaps are trying to spend a little bit more per, a little bit less per head for the meals they are producing. But no, if you, if you seek out and you market certain categories, particularly, fairly well refined hotels, certainly fine dining restaurants and pubs as well, pub grub is something that's very much in the summer months.

What we do find is that there's a slight drop off in kind of January and February to sales across the board, not just because people can't afford it, but because that's, generally speaking, when chefs are spending less. Anyway, I would just add to that that there are not high volumes of Mangalitsa available in this country. So I could not pick the phone up tomorrow and buy ten Mangalitsa off anybody, anywhere. And then another ten next week, and then another ten next week. So it's a real it's a prized product. So a chef will know that they're going to have to use it wisely. So lots of chefs like to do specials. So they might run a special for 2 or 3 weeks.

And they're buying one, 2 or 3 pigs, you know, to to sell Mangalitsas in high volume. We're not quite there yet. If anyone's thinking of producing 20 Mangalitsa pigs to sell a week at the moment, the only place you'd sell them is probably Japan. So, you know, it's a it's a rare pig. That's why it drives the premium price as well as its quality. Okay, great. At what age and sex do you use? I suppose sex is both okay. Yeah. I mean the it's all about getting it to the right shape and weight So you generally judge a pig. Well, I look at a Mangalitsa by eye. Boys tend to develop slightly slower than girls as far as putting on fat.

But boys will be a bigger framed pig first. So, generally we like to slaughter them, so they're at a dead weight of around 75 to 80 kilos, which is probably 100 to 105 live weight If we take a two year old pig to slaughter, that's going to be nearer 140 kilos and come back at about 120 dead weight How do you remediate the rooted soil? Do you do anything like do you cover it or anything like that? Nope. Again, it's, Sorry. I spend a lot of time in the woods, and that's fine. And we basically view the pig as a, tractor that fertilizes So they're in there. They're turning it over, and if you'd leave them for the right time, you can see. You can see what damage is being done if you want to call it damage. So once everything's been rotovated and all the grazing has been picked up and some of the saplings have been knocked down, then I can tell it's time for them to move on.

And so at that stage, it's a bit like a slow rotovation of your back garden before you plant out again next year. What feed do you used for the pigs at their different life stages? Well, we we only use one type of feed. We use what's called a sow roll. So that's a balanced pellet. That's just a general pellet that's got the minerals and the protein that the pig needs. Everything else to supplement by the woodland. I don't I've never really gone into buying food specific for piglets, food specific for pigs that have come in to be finished and fattened up. I tend I mean, it's my personal I've got nothing against it. Everyone's got their own choice.

But we personally use one type of food from the minute the piglets start picking at their mum's food, right up until they're ready to go off to slaughter. What you do do... There is a little bit of a judgment call of how much, how much we feed, at what time. It is a completely different question. Again, I tend to judge that there is a strict equation for commercial breeders. How much in weight and feed you will give a certain age. Pig I do it all by eye I look at the pigs condition, I look at if it's growing outwards and upwards, I look how much fat it’s putting on. And at that point I'll either draw the feed back a little bit or I'll up the feed a little bit. It's paying attention to what they need, not giving them what you think they need do. If I can just, that's partly as well to ensure that you're getting the right fat distribution.

Distribution way you want it. Because if you can. Because basically, as the pig changes shape itself, it as it's growing, then what you're looking is for specific extra fat distribution around the belly or around the hind legs. And and Phil tends to, feed based on which areas need a bit more. Yeah. There's there's time when you want them to grow upwards and outwards, and other times when you want them to put fat on. Yeah, yeah. How many acres do you have for your 100 pigs? And what size paddocks do you break that down into. And how frequently do you rotate them from paddock. So we've we've got just over 30 acres obviously different enclosures.

Again, when you're creating the enclosures in woodland, you tend to have to follow what the woodland telling you is about where you'll get where you can physically cut through and make an easy access to put a fence in. So our smallest enclosures are for farrowing. So when the sows are preparing to give birth, we'll put them in quite small, contained enclosures. Maybe 150m², where if we've got groups where they're growing on from, say, 4 or 5 months old, they might have, you know, up to an acre, an acre and a half, and then there's various size groups in different sizes, but generally, I think our biggest enclosures on plot two that we did were about 4000m², and that took up to about 18 pigs, (can people) We rest at resting, you know, it depends.

Again, the same as when we decide to put more feed into a pig. We pay attention to what the woodlands telling us. If it's had enough pig in it, then it's time to get the pigs out. So it's paying attention to what the ground's looking like, whether it needs to rest as part of the project study. We’re keeping for... what we're calling plot two, which is particularly for the scientific study, as opposed to generally how we've chosen to rear them so far, we're sticking to the six months of pigs in, and we've got as well as our control paddock, we've got, a high to a higher high density and a low density of to two different paddocks and then a third paddock with just a couple of adults. And so we're hoping that by the time all of the information in the data comes back, we can see if there is a difference in stock density level for pigs kept for a six month period. Great.

But you know what? What the kind of parameters are as far as the stock density goes Super! Can people still walk through the woods? Yes, they can. And they do. So as I say, it's on the estate and it's not exactly a public pathway, but over time, people tend to make things a public pathway because they walk there often. So it becomes a public pathway. But obviously as long as they respect that there's pigs in there, which isn't difficult to spot once you get into that piece of woodland. We're quite fortunate. We've got a we've got like a track that runs all the way around the outside, which is fenced on both sides. So we can not only drive around that for access to all the enclosures that anyone wants to walk around, they won't accidentally find themselves in an enclosure with an angry boar No, the our boars are angry. They're all very soppy.

The biggest danger to people coming in is the electric fence, but they'd probably only touch that once. And obviously there are signs up as well. Yeah. Are your Mangalitsa Mangalitsas..... leaner than conventionally reared ones? Oh, I didn't hear the first part of that. So. Okay. Are your pigs leaner than the conventionally reared ones? No, that that's the opposite to that. They're fattier. So but the lean is a deeper, richer color. Its protein value is higher, its flavor is richer. So what you would get from, say, you had an eight ounce commercial pork chop, you would probably only need a four ounce Mangalitsa pork chop of lean to give you exactly the same protein value. If that made sense? Yes it did. Okay. How do they impact the bluebells in the woods?

They don't actually like bluebells. Yeah. It wouldn't be anything personal. We don't have a lot of bluebells in the woods, to be honest. This is something that's going to be interesting to watch over the coming years as the areas are opened up by the coppising of all the saplings and the grasses start to come back. If the bluebells come back, I will keep you posted. But it's not really a bluebell wood. Okay. Foxgloves. An awful lot of foxglove. Yeah, yeah. It's foxglove. Okay, okay. What color is their poo with an 80 to 20 feed, forage, split. It's, I would say it's like a chestnut, chestnut chestnut brown. Thank you. Perhaps the color of my hair.... Not quite, quite a bit lighter. Yeah. Roughly. What would be the percentage of their diet in grain versus the foraging?

Well, well, that would vary times of the year. So as Melissa explained, when pigs are put into, a fresh enclosure or one that's been restored and rested over a few months, then they're going to have bits of everything and they're going to have fresh grazing, fresh roots, brambles, lots of bugs. And then come the autumn they're going to have chestnut, sweet chestnuts, acorns. So the percentage then will go up. That probably wouldn't put them off their pelet dinner. And I wouldn't necessarily deprive them of that, but we've found that we can definitely feed less through mid-summer, to probably almost up to December, and that probably is about 20% less. So I guess you could say to 6 or 7 months of the year, the woodland supplements probably 15 to 20% of their diet.

Do they eat the rhododendron or just root them up? No, they don't, no. They root them up They don't. Rhododendron, as I think most people know is poisonous and pigs have very aware of what they can and can't eat. So they'll just root what's underneath them and then we'll just as they loosen up, we'll we'll pull them out. I mean, it will take a long time. There's a lot of rhododendron in this, in this neck of the woods, excuse the pun. But it is starting to clear. Are you breeding them year round, or do you aim to have litters in autumn and spring? Now, I'd love to just be able to breed them in the spring and then stop in the autumn.

But because we're continually expanding the herd, we probably have a new litter every two weeks, nearly all year round. Let's see... Oh, I'm getting to the end here. Okay. Can you can you give some information about the charcuterie courses that you offer? Yeah, basically. Well, it started really a few years ago with chefs, mainly. So sous chefs and chefs from, hotel groups used to come down, to be able to learn and add to their own culinary skills. And then we decided to kind of officially offer courses to the general public as well as, hospitality workers. And, so, yeah, we do either just a one day course where you can just come and have a look around that includes, a pig site visit, as well as having a look at the production units and what we do.

And then equally, if you're really, really fascinated by it and you want to have a go and have a bit more hands on, then we can provide a three or, 3 to 5 day course, which would literally be you coming in curing and netting, making salamis, getting involved, perhaps not with the butchery....? Maybe. Maybe have a go at butchery if you feel confident enough. And the last one that we provided, was last year for, a charcuterie company who are also rearing Mangalitsa based in Ireland, so they were with us, there and a couple that and the owner, of their business. So they were with us for a whole week. Basically learning the techniques. The main reason why we why we want to be able to it's not just educational, but it's also really to get kind of the love of the Mangalitsa going Because for us, it's very important that there are more Mangalitsa breeders.

And also I think you, you know, I think it's something that is a hands on thing that you need to have a bit of help if you want to produce your own charcuterie from people who have been doing it for quite a bit longer. There's when we started, even though we knew the techniques from being in Spain and we learned them in Spain, doing in England was was quite different from hanging a ham up in a cavern or a cave or you know, or your attic in Spain or your cellar in Spain. Because getting the conditions right is vital to the charcuterie production. And that's just lots of little, little things, right that you've learned over the last ten years that are just really quite important, from not getting little pockets of air and the salami from not. Yeah.

I mean, all the way from the beginning to to now, you always, always. Someone's always improving. Yeah. We had some questions about the fencing. Is there an electric wire at low level on the fence. What height is the electric wire and what sort of voltage is necessary for them to respect the wire? We tend to put I mean pigs don't look to just walk through the fence, then the the snout down there looking for something interesting on the ground. So generally if, the only time pigs ever get out of the enclosures is if the electric fence has gone down for some reason. So if the electric wires touching the actual fence itself. It will short out And a pig would just keep burrowing. And all of a sudden, if realized that the electric is not on and his head's under the fence, so I might as well keep going. So we tend to put the electric wire about ten inches above the ground.

And that. And that's on a pulse electric fence. So about every second it send out a pulse. So it's not a continuous. So continual shock. It's just enough just to make them aware it's there. And our battery is probably 10 to 10,000V. It at the most ten volts, sorry at the most. Very occasionally for the our boars we've only got a couple of boars We'll put a higher high one up as well. Just put a second one up at about 4.5ft high, because boars tend to want a look over the fence if they can smell the ladies. Are you afraid to have boar flavor in the meat? If you take a boar beyond 12 or 13 months, it can suffer from what's known as boar taint.

Now there's an argument that says that Mangalitsas don't have boar taint And to be honest, I've never really noticed it in any animal that's around 12 or 13 months. But I have never butchered and tasted one. That's over two years. Any any older pig that we process will always be, a female. Do you castrate or separate males and females post weaning? At the moment we separate. So the wood's pretty much divided into girls, boys and mums. We tend to find if there's 50m between boys and girls, that's a big enough gap. Pigs eyesight isn't very good. So the boys don't lean over the fence trying to see what's 50 or 60m away because they struggle to see what's 10 or 15m away. So it's more the smell. So we try and keep a 50 meter gap between them.

How easy are they to handle and move? The the best, the best way for any animal I believe, is from an early age. Get them used to getting on a trailer so we move. Will obviously move the mums around regularly when they're in with a litter of piglets, and it's time for them to be weaned off. The mum will almost open the back of the trailer herself to get out, because she'd be keen to get out of the nine, 9 or 10 piglets. And then we tend to move the piglets about 6 or 7 weeks after they've been separated with mum, when we need to divide them into girls and boys. And if they're hungry and there's plenty of straw in the back of the trailer when they move up. I mean, there's pigs in the woodland that we've that we've had for a few days now that I could walk around the woods to, to take them to their new enclosure. Now, obviously there's always one that just doesn't want to go if it's a bad day, if they're in a bad mood, if they don't want to know, they don't want to know. But overall practice makes perfect. Just try. And even if you just move the trailer up to the gate and feed them every couple of weeks or so once a month, just so they're used to getting off on and off a trailer, they're no problem. And then and general handling as well. Just being in with the piglets, really getting used to the human contact is something that we've always we've always done anyway.

Do you ever sell your piglets? No. It's something we'd like to do. We're increasing with new pedigree lines at the moment because obviously the bloodlines are running a bit thin in this country because there aren't many Mangalitsas in the country. So we will be looking in the next year to 18 months. Once we bred from these new pedigree bloodlines, to find other people who want to help expand the breed as well. So at that point, we will happily sell piglets, but only when the new bloodlines and we want to strengthen them so we don't really sell them to people that are not pedigree bloodlines that are rare because we want to use them for our charcuterie. But we can always put you in touch with other breeders that do what we have done in the past is loan out piglets and then take them back when they're at slaughter age. So we basically buy them back.

This has been so wonderful. Thank you both, Melissa and Phil, for your time today. The reviews at the end are much gratitude. People really appreciate, the value of the information that you have brought today. So really, really appreciate. And I know you put a lot of work into that slide deck, so thank you so much. You're welcome. Thank you for attending and listening and being interested. Yeah. Thanks, guys. So many of you obviously can contact us by email if you have any, any questions at any time. Great. And for the listening audience, we will make a recording and we will issue it to you by email. So and please do share it with other people. All right. Super. Thank you. Bye. Thank you. Bye Good night everyone.

Synopsis:

This webinar, hosted by Sheila Cooke of 3LM, features Melissa Masters and Phil Beal from Beal’s Farm. It explores woodland pig farming and artisanal charcuterie production, focusing on the Mangalitsa breed. The presentation covers how integrating pigs into woodland agroforestry systems promotes ecological health, animal welfare, and premium meat quality. Topics include the benefits of rotational paddocking, soil regeneration, biodiversity enhancement, natural feeding, and the market potential for high-quality, ethically raised pork. They also highlight funding possibilities and practical considerations for setting up woodland pig systems. The message is clear: ethical, sustainable farming can be both profitable and restorative.